Division in the Body

Jesus destroyed the division between Jew and Gentile. But today, many of us are rebuilding a dividing wall of hostility, brick by brick. In levying new regulations on one another, we sacrifice peace, unity, and wisdom from above. What's a better way?

By Jamie Turco and Jeremy Schurke

In Ephesians 2, Paul reminds the Ephesians of what Christ did for the Gentiles, who were once bitterly divided from the Jews—

But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far away have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility, by setting aside in his flesh the law with its commands and regulations. His purpose was to create in himself one new humanity out of the two, thus making peace, and in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility. He came and preached peace to you who were far away and peace to those who were near. For through him we both have access to the Father by one Spirit. (v. 13-18, emphasis added)

Today, we aren’t arguing about circumcision. We don’t question whether we all have access to the Father through Christ. We accept and give thanks that that wall has been destroyed!

But within the body of Christ, many of us—even without realizing—are rebuilding a wall of division and hostility, brick by brick. Instead of “he himself” being our peace among Christians, we’re levying new commands and regulations on one another, and the price is unity and peace.

Current Events Over Eternal Ones

There’s no shortage of opinions around us on everything from vaccines to masks to race relations, sexual ethics, technology use, immigration, politics, education—the list goes on. We find opinions online, at the dinner table, in the church lobby, and in the conference room. But there is a shortage of fruitful conversation and listening to understand. And people are walking away from the church because of it.

Consider the past 18 months in your own life. Have you or someone you love left a friendship, small group, or a church over a different view on a current event? Or have you distanced yourself to avoid the issue altogether?

Christians aren’t going to agree on everything, nor should we have to. We come from a variety of experiences, backgrounds, personalities, and circumstances.

The question is not: How can we all agree? The question is: What’s different about Jesus followers than the rest of the world? If the conversation goes—Oh, we disagree? You’re wrong. Bye.—then there isn’t any distinguishing feature about us. If a tone of hostility, sarcasm, and contempt marks our interactions online and in person, then we look just like the world. Jesus' death on the cross to bring us together in Him is obscured.

Part of our challenge is to adjust our focus. When we focus more on current events than eternal ones, it becomes difficult—if not impossible—to overcome our differences under the umbrella of Jesus Christ.

If, however, we let Christ be not just a common denominator, but the defining, common denominator of our lives and identity, then there’s room for all of us under that umbrella, as the lesser things get washed away.

Adjusting Our Focus

How can we recognize that we’re letting lesser things become a dividing wall of hostility? There’s no one symptom that looks the same in all of us, but there are some common side effects. Are you experiencing an uptick in anxiety, anger, indignation, offense, or hopelessness? Are any of your relationships suffering?

If you’re feeling divided from others in the body of Christ over current events, it may be time to do an audit of how you’re spending your time. Multiple studies have shown correlations between mental health and screen time, specifically with social media platforms. As our amount of screen time goes up, so do our feelings of anxiety, depression, and isolation—made worse by algorithms that drive us further and further apart.

Is there a late-night news show that you could replace with seeking wisdom and truth from the scriptures? A social media list of friends that you could pray for instead of scrolling past? A podcast that you could sub out for hanging out with a friend?

Of course, we should concern ourselves with the current realities that others are facing. But we weren’t created to carry the whole world’s burdens day in and day out, with new ones coming in by the minute. The load is too heavy.

What we can carry, from a place of love, is the burden of a sick neighbor, or a grieving coworker, or a buddy who’s struggling in his marriage. The more you can zoom out on current events and zoom in on the events in the lives of those around you, the better.

Show up for the real people God has placed in your path.

The Pursuit of Peace

You’ve decided on some needed adjustments and made them. Unity in Christ is your focus. You’re engaging with real people and caring for them. You’re feeding yourself with scripture and not just news.

Now how do you overcome some very real differences to pursue peace with others?

One man we know locally shared this story about how he's fighting a desire to pull back from church:

“My wife is on immunosuppressants to treat a disease that causes lung damage so when COVID cases skyrocketed in our area, we started wearing masks again to church,” he said. “Recently, I saw a social media post from a guy at our church saying that parents sending their kids places in masks should be arrested for child abuse. I didn’t respond online, but it stayed with me for a few days, bothering me. That Sunday when I dropped my son off, wearing his mask to help protect his mom, guess who was the volunteer in his Sunday School classroom that day? Same guy. It was uncomfortable. When the next Sunday rolled around, I admit I just didn’t feel like dealing with it. So for the first time in months, we stayed home instead of going to church.”

In this scenario, both men serve in the same local church. They see each other on a weekly basis and have mutual friends and a shared love for Christ. And yet, through one’s careless words and another’s passive silence, a dividing wall is erected. What’s the alternative?

Confrontation—while much harder than gossip, passive aggression, or avoidance—is the prescription given to us in Scripture (Matthew 5 and 18). When done right, it’s also the least likely to lead to a lasting rupture.

As Christians, we all have a role to play in making the church a space where open dialogue is promoted about the issues that threaten to divide us. When the church isn’t a space for it, then the hairline cracks become devastating fractures.

Pastor Kyle in Arkansas shared:

“We’ve had some real division in our church, people leaving on both sides of the political issue, and so much of it could have been headed off if they were willing to have a conversation and listen to other perspectives as opposed to brooding for 12 months and then leaving.”

Confrontation—and how we do it—is the component that makes us peacemakers and not just peacekeepers. It’s our responsibility to go to each other, face to face, and share our concerns or hurts when they arise, and it’s our responsibility to respond in a way that is considerate and gracious when confronted.

When we disagree or take a stance on something, what should mark our discussions as Christians isn’t having better putdowns, cleverer comebacks, or smarter solutions. It shouldn’t be digging in our heels and refusing to hear other viewpoints.

Instead, James 3:17-18 describes the kind of wisdom that should mark us:

But the wisdom from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, impartial and sincere. And a harvest of righteousness is sown in peace by those who make peace.

Antidotes to Division

Who do you know that embodies wisdom from above? Who around you is known for being pure, peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, impartial, and sincere? Does someone come immediately to mind?

These qualities aren’t valued by our culture—or even, if we’re honest, always valued by us. No, we’re often drawn to the loudest, smartest, and most dominant voice.

But there are two things that we can start cultivating now that not only build wisdom, but also serve as antidotes to division: humility and relationship.

It’s a cycle of sorts—in humility, you form relationships with those who think differently than you, and in turn, you are humbled. The same is true in our relationship with God; it doesn’t take long before we realize that what we thought we knew and understood was incomplete. We grow because of that discrepancy, not in spite of it.

Humility and relationship are the antidotes to division in the body of Christ.

Here are some questions to consider and practical steps you can take this week to build humility and relationship.

For Reflection:

- Are you willing to admit to someone else that you’re not sure about something?

- Are you able to acknowledge truths in what others are saying and experiencing?

- Do you believe that other perspectives and experiences can ultimately enrich your life and even your faith?

- Do you trust that God is in control?

Action Steps:

- Invite someone who feels differently than you about a current event to lunch or dinner. Ask them about their experiences. Practice listening for the purpose of understanding, not to change their mind.

- Set some limits this week on screen time and online discourse; replace it with something that feeds you spiritually—worship, journaling, prayer, or reading.

- Think about someone in the body of Christ with whom you disagree. Are you building the dividing wall higher or working to tear it down? What’s your right next step in that relationship?

God’s People

When Christ destroyed the dividing wall between believing Gentiles and Jews, there was a powerful ripple effect.

In Ephesians 2:19-22, Paul continues:

Consequently, you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of his household, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone. In him the whole building is joined together and rises to become a holy temple in the Lord. And in him you too are being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit.

As God’s people, we must choose. Will we tear down or contribute to a dividing wall of hostility? Will we keep others out or invite them in?

Let’s join together and rise—not because we have no disagreement among us, but because in Christ, we are being built together as a dwelling place for Him.

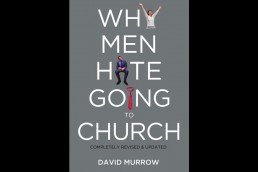

David Murrow's Why Men Hate Going to Church

A Review by Louis Schieferdecker

Intern, Mirror Labs

“Modern churches are women’s clubs with a few male officers.” David Murrow makes observation after observation like this about the church in his book Why Men Hate Going to Church.

Early on, Murrow lays out how the church has leaned toward the feminine in a variety of ways throughout history and why it keeps trending that way. Then he explores how this trend is impacting men—and ultimately how the church can better reach them.

At first glance, I was immediately curious about this book because of the title, because I, too, hate going to church. As I read this book, over and over again I found myself being “seen” by the author. As he described the issues and pain points of men, it mirrored how I thought or felt about different aspects of church. At several points I found myself deeply moved as the book reoriented different experiences I’d had in the past but couldn’t quantify and heal from at the time. I wouldn’t say this is the book’s goal, but it was definitely an unintended benefit for me reading it.

One of Murrow’s points that stood out to me is how well he addresses the feminine leanings of the narrative of the church’s theology and practical ecclesiology—and how the narrative does so to almost the exclusion of the masculine.

For instance, Murrow describes how the church today by and large wants to operate primarily as the family of God. This is well meaning and good on its own, as it is core to the church’s identity—so much so that it’s the first line of the Lord’s Prayer: “Our Father.”

However, Christ didn’t come to proclaim the family of God, Murrow argues, but rather the kingdom of God. There is a huge difference between the mentality and culture of the two. Murrow makes the simple point that “Kingdoms are about doing. Families are about being.” In that dichotomy, one immediately senses a split between the masculine and feminine.

That’s not to say that the kingdom can’t or shouldn’t include families—in fact they are what kingdoms are built on and through. We are saved as we are grafted into the family of God to become the kingdom of God. However, looking at the current church culture, it is entirely clear you can have a family of God mentality without a kingdom of God one, and Murrow asserts this is one of many reasons that men are suffering in the church.

Another area in which Murrow talks about a narrative shift to the feminine is what aspects of the gospel are often emphasized. The gospel is now primarily a love story, and not a call to action. So much of the church’s corporate worship is about how much God wants us, our value, and the price he paid for us—or in reverse, about how much we love Him.

When was the last time you felt or saw the greatness of the actions of the kingdom, or stood in awe of the power of God and his work in and through his people? We sing love song after love song, read book after book on God’s love, and talk about religion in romance language as the norm—“Jesus, lover of my soul.”

Consider the motifs of the Lion of Judah and Lamb of God. As the protestant church almost singularly focuses on justification and God paying the price, we have made the Lamb of God the overwhelming motif. This part of the gospel is harder for men to grapple with emotionally than it is for women, simply because in all the stories we’ve been told, we as men are instructed to be the heroes. The man rescues. The man does the saving. And oftentimes, as a result, the man gets the girl. In short, men want the prize, but many men don’t know how to be the prize.

Let me be clear, Murrow is not talking about cherry picking, nor is he saying that these aspects of the gospel are not good and true; rather that, again, we have chosen to emphasize one to the near exclusion of the other. In all of this, Murrow makes no case for changing the gospel at all; rather he is calling for a re-embracing of the masculine parts of the gospel, as he believes that men are desperate for it.

As I can’t summarize the entirety of the book here, here are some of the other points I found interesting and helpful. First, he discusses how the economics of the church continually drive the church to skew feminine; women are more likely to go to events, read books, do Bible studies, sing in worship, and just attend in general. Therefore, with women driving the demand in the church, it reinforces this trend.

Second, he aptly points out that men won’t play if they don’t have a fair chance to win. That seems a bit obvious, but when you consider what a church needs from its people to operate, you quickly see how some men could feel as if they can’t compete for those roles, such as the church nursery, music, cooking, and event planning. Oftentimes, if men feel inadequate, they simply won’t play. Sadly, other than a church work day, most churches simply don’t need what are typically viewed as more “masculine” skills.

One criticism I have with the book is less about the content that is there and more about what isn’t there.

For example, this book treats masculinity as a bit of a magic bullet to solve the problems in the church as a whole. That is to be expected to a degree, as this book's main assertion is that masculinity is desperately needed for the church; but while it is an essential ingredient, it is not the only essential ingredient.

Also, I think it's important to emphasize a healthy process and balance in the church that embraces both masculinity and femininity. The goal should not be to create a hyper masculine or “macho” church, as that is dangerous in a different way. While I don’t think Murrow is asserting anyone should go in that direction, as a reader I can see how someone might fall off the other side of the horse by overcorrecting. It needs to be couched and considered a bit more.

I’d recommend this book to church leaders and men who feel disenfranchised in their experience within the local church. It creates contact points to rationally and emotionally process those experiences and invites everyone to the table. Importantly, it also opens the door to conversations about how we present the gospel, how we create the culture of relationships in the church, and it provides useful data for how men have functioned (or not) in the church in recent history.

I think it would also be beneficial to church development conversations, both in committee and through seminary training, simply because it creates categories for conversations that no one is having but are desperately needed.

While this book seeks to amplify the masculine in churches, I in no way read it as a polemic against the feminine. Instead, Murrow is aiming to bring the masculine and the feminine together for a fuller, deeper, and truer experience.

On the whole, I would highly recommend this book as a great tonic to some of the ills in the modern church and would say it is well worth your time to consider.

"I Have No Plans"

Empathy requires more than observation. It means coming emotionally along side another person. In some small and existential way entering into their world, seeing and feeling through their eyes and emotions.

Few parents, marketing gurus, and ministry professionals have done this adequately with the emerging generational cohort of millennials and Gen Z young people.

As an academic student of millennials, even I missed it. In my book The New Copernicans: Millennials and the Survival of the Church I listed seven characteristics of the new Copernican frame shift. There are actually eight as I missed one, and it’s a big one too. I learned it from a pink-haired, millennial, gay, Unitarian pastor wearing a “Black Lives Matter” T-shirt. He told me that what I had written was correct, but that I had missed one because I didn’t live life within a millennial frame.

The missing characteristic is anxiety.

One blogger wrote:

This year during Youth Sunday, a sixteen-year-old girl stood in the pulpit. She was barely visible, given her small stature. From my view in the choir loft, I could see her knees trembling. Getting her up there was a challenge, but now she stood before our congregation and shared about her struggle with mental health issues. (…) “Anxiety is a relevant and personal battle many of us face,” she said passionately. “We need to start talking about it in the church.”

By “talking about it,” she meant something more than providing pat spiritual clichés and quoting Bible verses. We need to face, acknowledge, and lean into the paralyzing fear that besets an entire generation of young people.

The statistics are alarming among young people: the depression, suicide, loneliness, and hopelessness are the air they breathe. And this was before the isolation and disruption of the pandemic.

Young people are not returning to a new normal with any sense of optimism. Young people are leaving the support systems of family and school to enter into a world cosmically alone and adrift.

It is also the time when the culturally assumed responsibilities of vocation, marriage, and parenting loom on the horizon. It can no longer be assumed that a church community will pick up the slack. It is not even clear how one will make friends in a post-college life. The isolation and loneliness are palpable and paralyzing.

Here are the words of Allyson Fea, a recent graduate of Calvin University (2020) and daughter of Messiah University Professor of History John Fea. If this is what “privilege” sounds like in millennial land, we’d better wake up to the perceived and real challenges facing this generation. Pat answers are not going to help anyone—nor is ignoring this reality.

Rejection letters, dried-up funding, and social isolation add up to more than “First World problems.”

I am tired. I do not get enough sleep (six hours on a good night), but late nights are not the only explanation for the dark bags growing under my eyes. It is the constant worrying and uncertainty about the future that drains the pep from my step.

I graduated college in May 2020.

When the pandemic hit, I had senioritis and thus welcomed a two-week break from classes. Two months later—my “graduation day”—I was sitting in a friend’s living room watching a live-streamed “ceremony.” We celebrated our accomplishments and grieved the end of our senior year. My family was 485 miles away in quarantine.

But I knew my losses paled in comparison to what people suffered during the pandemic. Mine were so-called “First World problems.” So I buried them under other COVID-19-related woes and tried to stop feeling sorry myself.

That is until the questions began. People always ask them with a sense of innocent curiosity: “So you graduated with a degree in [insert major here]. Good for you! What are you going to do with that?”

Instant panic. Do I rattle off a list of all the possible jobs one could do with a double major in history and psychology? Should I spin an elaborate, fraudulent tale about my five- or ten-year plan? Maybe I could use a smile or some big industry words to distract my inquisitor, giving me an opening to change the subject?

Anything to avoid the truth: I have no idea what I am doing, no plan for the future, and no progress to show.

I have spent the last year binging Netflix shows and trying out new air-fryer recipes in an effort to avoid these well-meaning but anxiety-producing questions.

What a time to enter “the real world”!

The questions about the future, and the social pressure to forge a path ending in middle-class comfort, can be unbearable. Recently a good friend asked me if I had started investing for retirement—she says she is on track to be a millionaire by age sixty-five. I reluctantly admitted that I don’t even have a stable income. Friends who majored in marketing, nursing, and business are already talking about career advancement, 401ks, getting married, and buying a house in the suburbs. I am not interested in any of these things right now, but I still feel like an outsider looking in when we get together for coffee.

It is not easy to find a vocation when internships are limited, job fairs are on hiatus, and graduate school funding has dried-up. Endless nights in the college library seemed worth it when I thought about the possibility of going to graduate school on a full ride. Then I learned that every school that accepted me had cut funding for incoming students. I guess I’ll take another “year off.”

It is also hard to find my way in a post-graduation world without the human connections one gets from hanging out with friends, traveling, or going to church. It has been so long since I attended a friend’s birthday party, worshiped in a brick-and-mortar church, or even hugged my grandparents. How much longer can I self-isolate indoors with nothing but my anxiety about the future to keep me company?

I could keep chronicling the trials and uncertainties associated with living out the formative years of one’s life in the midst of a pandemic, but that is not why I am writing.

I am writing to normalize the feelings of sadness I have suppressed because I knew others had it far worse than I do.

I am writing to normalize the fears about the future and the uncertainty that comes with it.

I am writing to normalize the frustration I feel from people in my life who cannot understand these fears.

I am writing to normalize the unhealthy, self-directed anger I feel for not being able to just “figure it all out.”

I am seeking experiences and learning opportunities that might point me in the right direction. But it is still normal to feel these things.

I don’t have a five-year plan. I don’t even have a one-month plan. I don’t know what I want to do, or where I want to end up, or how I am going to get there. But I am also starting to embrace the uncertainty of the post-pandemic graduate life. This means giving myself grace when doors close, rejection letters flood my inbox, and failures pile up. It’s okay to grieve the loss of the little things, and it’s comforting to know that I am not alone in my anxiety.

So the next time your great aunt’s second cousin twice removed asks you about your future plans, tell her that you have no idea. And get a good laugh when you see the stunned look on her face.

What is a blog? Good q. Hold on, let me go look it up real quick…

After some internet sleuthing, here is what I found:

- Online personal reflections, comments, and often hyperlinks, videos, and photographs provided by the writer.

- Typically relates to a particular topic and consists of articles and personal commentary by one or more authors.

So, yes, this is the Mirror Labs blog. A place where you can find my (Jeremy) personal reflections and social commentary revolving around the issues that young men care about. From time to time, I will include links to other resources and different types of artistic media.

This will also be a place where other authors can write and share their thoughts.

My goal is to deeply reflect together and provoke new insights. I'm excited to get started, thus why I wrote this first blog. Welcome!

Jeremy Schurke

Director, Mirror Labs

May 18, 2021